I used to be one of the biggest fans of organic food companies here at The Motley Fool. For the past seven years I've spent over half of my time living and working on an organic coffee farm in Costa Rica; from the tours we give, I've seen firsthand the excitement everyday Americans have about reconnecting with their food.

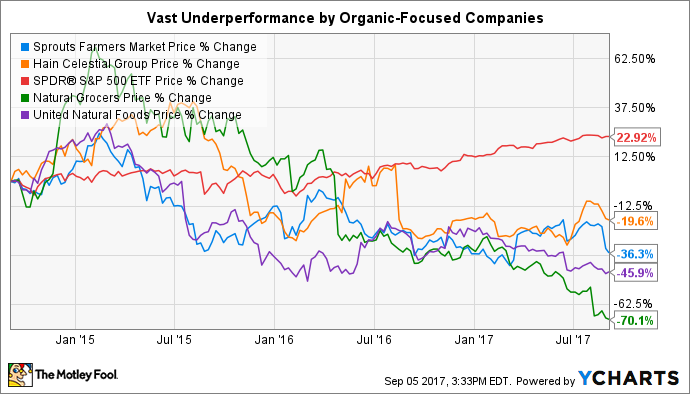

But what makes for a great movement does not always make for a great investment. Because there's no discernable moat when it comes to organic food, I fervently believe that you should not spend your hard-earned cash investing in organic food companies. Over the last three years, it's been a losing proposition for investors, and I don't think that'll change.

And this is even ignoring the fact that the 800-pound gorilla in the room -- Whole Foods -- was down 50% from its 2013 high before it got bought out by Amazon (AMZN -1.44%).

Behind this belief are are two very simple premises:

- There's nothing that makes one company's organic goods better than another's, at least on a blind taste-test.

- The brands in the organic realm are simply too young to have a history of proven pricing power over their competition.

As cynical as it might be to say, these two factors alone mean that investing in companies that are focused on organic goods -- like Natural Grocers, Sprouts, Hain Celestial, or United Natural Foods -- will likely be a money-losing proposition.

We've come a long way

As my grandma says, "It's funny people focus so much on 'organic' food these days. When I was a kid, we just called it 'food'." For the most part, she's right. While some elements of chemical farming were well underway back when she was growing up, it was nowhere near the level it reached just 10 years ago.

That's why, in hindsight, it's absolutely laughable that the Federal Trade Commission almost blocked the merger of Whole Foods and Wild Oats. Seriously, were we so far removed from naturally grown food that we were worried a small grocer could corner the market?

It just goes to show you why Whole Foods did so well for so long before it absolutely caved in: it pursued a niche that few were paying attention to, giving it the whole sandbox to work in. But as soon as competition caught on, the market responded by giving incentives to farmers to grow more organic produce, and voila, Costco, Wal-Mart (WMT 1.31%) and Kroger (KR 0.37%) all had their own private-label organic brands that were selling like hotcakes at lower prices.

That underscores the fact that for consumers only worried about the "organic" label, there's going to be a race to the bottom in terms of pricing. Amazon's entry into the fold will only accelerate that transition. And while that's bad for publicly traded organic companies, it's net-net positive for us: food is being grown in a slightly more healthy manner, and it's more affordable than it was before.

The dark underbelly of organic

But my time on the farm in Costa Rica has taught me another thing: even the high-end customers who go the extra mile to make sure they know where their food is coming from will eventually shy away from Whole Foods and its ilk. The reason: the organic movement has effectively been compromised.

Could this be where the high-end niche is filled? Image source: Getty Images

By that I mean we have scores of factory farms that are following the letter of the organic law, but certainly not the spirit of it. We know of several coffee farms in Costa Rica that still use "organic" pesticides and herbicides and maintain a strict monoculture but get to sell their beans for the same elevated price as those that don't. And that's just coffee; the examples in other areas are legion.

And that brings me back to an article I wrote in 2013, The Paradigm Shift in American Food. I mostly focused on how organic was becoming more important, but included a caveat at the end:

Taken to the extreme, [farmers' markets, community supported agriculture, and the locavore movement] could mean the end of investing in food companies altogether as it would be the independent, local farmer providing the vast majority of food for consumption.

While I still believe the "vast majority of food for consumption" will fall outside this circle, I'm starting to believe that the high-end niche will not be satisfied by those wearing suits claiming organic superiority, but by those wearing overalls and suspenders who are actually doing the hard work of organic farming -- and inviting their customers to come see for themselves.

Pinched from both sides, I don't think investing your money with organic companies is a good use of capital moving forward.