Among high-yielding stocks, business development companies (BDCs) are some of the most common income investments that few people understand. These companies can boost the yield earned from an income portfolio thanks to their outsize dividend yields, which frequently top 8% per year.

But before diving in head first, it's important to understand the unique risks and rewards of investing in these stock market oddballs. Here's a primer on how BDCs work, and how to analyze a BDC before investing in one.

What BDCs do

BDCs are in many ways just closed-end funds that make loans to, and buy equity stakes in, mostly private businesses around the United States. They invest in companies that can be as small as a neighborhood cafe, or as large as billion-dollar businesses with household names.

BDCs fill a void that exists in the financing marketplace. Banks are a go-to provider of capital to small businesses, but they generally aren't interested in particularly speculative or risky credits. Wall Street is the preferred provider of speculative investment capital, but it generally isn't a good fit for smaller businesses. BDCs fill the gap by providing capital to smaller businesses that aren't large enough for Wall Street's financing machine and are too risky for commercial banks.

That said, keep in mind that a "small" business isn't exactly a corner convenience store. Many BDCs are invested in companies that generate more than $50 million in annual EBITDA and have sales in excess of $100 million per year. Some well-known consumer-oriented BDC credits include Rug Doctor, Massage Envy, Benihana, Smashburger, Payless Shoes, and Toys R Us. All of these can be found in the portfolio of at least one, if not several, publicly traded BDCs.

BDCs typically provide speculative capital for growth or acquisitions, or to simply add leverage to pay a dividend to the business owner. As a result, a borrower who seeks capital from a BDC might pay an interest rate of 6% to 15% on a loan. In contrast, a regional bank might earn as little as 3% to 5% on its commercial and industrial loan portfolio.

Image source: Getty Images.

Who's the jockey?

BDCs are often referred to as "jockey bets" because the manager has the single greatest impact on the performance of the BDC over time. A BDC is only as good as the investments that make up its portfolio, and thus its management team's ability to pick good investments drives performance over the long haul.

Given short operating histories and limited public information, determining which managers are "good" or "bad" can be as much of a subjective exercise as it is an objective one. Many BDCs have operated through only one recession, which can make this analysis even more difficult. (Congress created the BDC structure in 1980, but the largest and most relevant BDCs today can trace their roots back to just the early 2000s at the earliest.)

The bellwether BDC, Ares Capital Corporation (ARCC +0.17%), has arguably proved its mettle more than any other on the public markets, as investors have more than 13 years of operating performance by which to judge its ability to manage its portfolio. Its ties to Ares Management, a leading credit manager, gives it the ability to source investment opportunities from a group that collectively manages $104 billion.

Of course, ties to a big-name manager don't necessarily lead to above-average results. Apollo Investment Corporation (AINV 0.93%) is part of the Apollo Global private-equity and credit complex, but its long-term record as a BDC is decidedly below average. Apollo Global has a reputation as a tough borrower in its own private equity deals, but you wouldn't know that from its performance as a lender through Apollo Investment.

History as a guide for the future

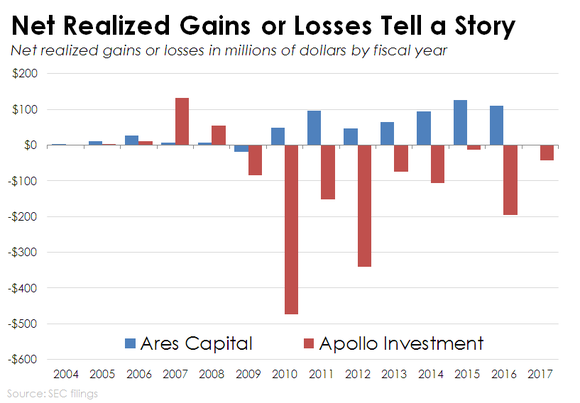

One of the best quick-and-dirty methods for benchmarking a BDC's underwriting ability is to observe and score its historical performance on investments that have run their course. One way to do this is to look at a BDC's "net realized gains or losses" over time. This figure is equal to the sum of gains and losses on all the BDC's historical investments that have been repaid, sold, or simply written off.

In a perfect world, a BDC will generate steady interest and dividend income from its investment portfolio, which can support large dividends to its own shareholders. In addition, it should also generate gains from appreciation on some of its investments to paper over its inevitable losers. Given the speculative nature of making debt and equity investments in private businesses, no BDC will bat 1.000 on its underwriting. Losses are certain, and BDCs must pay out all of their earnings, so a BDC needs gains from winning investments to make up for the losers.

A comparison of Ares Capital and Apollo Investment, which both launched in 2004, reveals very different underwriting performances. Ares Capital has historically generated realized gains, whereas Apollo Investment has generated sizable net realized losses. Not surprisingly, Ares trades for more than it did at its IPO, while Apollo trades at a fraction of its IPO price.

Image source: author. Data from the SEC.

Of course, knowing a little about a BDC can add some nuance to a view of its underwriting record. Ares Capital's gains were helped by its timely acquisition of a peer, Allied Capital, during the financial crisis. Apollo Investment's outsize losses during the financial crisis-era were largely driven by a big, bad bet on a hotel chain. When looking at a new BDC, I like to look at its portfolio during periods where its portfolio experienced large gains or losses as a starting place for understanding its historical portfolio.

While past performance is not a perfect road map for what the future will look like, BDCs that have grown shareholder value over the ups and downs of full economic cycles are likely to be a better cohort for investment than BDCs that have a record of making large investment missteps. Once underwriting cultures develop, they are very difficult to change.

Some other factors worth exploring:

- Unrealized gains or losses: This area focuses on returns on realized investments, but BDCs can have gains or losses on investments that haven't been repaid, sold, or otherwise realized. It's a curious matter when BDCs report significant unrealized gains but their realized investments have been mostly losers. It makes you wonder if the BDC is being overly optimistic about the value of the winners it hasn't yet realized.

- Management changes: If the BDC's leadership has turned over, it may be important to differentiate between returns on assets selected by the old and new management team. To give a topical example, when Oaktree Capital Group takes over the management of Fifth Street Finance (NASDAQ: FSC), it'll be important to differentiate between investments made by its old manager and its new manager. Complete management changes, however, are pretty rare.

- Portfolio strategy: Apollo Investment has historically generated its biggest losses in the most speculative debt and equity investments in hotels and oil and gas companies. In 2016, it announced a plan to invest in debt investments that are more "plain vanilla," while avoiding riskier debt and equity investments. One might choose to delineate between returns before and after a stated change in strategy.

What does the BDC own?

BDCs are generally split into two camps: equity BDCs, and debt BDCs. Each has its own unique pros and cons.

- Equity BDCs hold a greater percentage of their assets in equity (stock) of their portfolio companies. These BDCs tend to generate less recurring income and tend to have more volatile operating performance, just as a portfolio of public stocks generates less income with more volatility than a bond portfolio. On the other hand, these BDCs have potentially more upside, as equity investments can appreciate in value.

- Debt BDCs invest the majority of their assets in debt. These BDCs are likely to show less volatility in their underlying book value and tend to pay higher dividend yields, since they generate more routine interest income from their investment portfolios.

The vast majority of BDCs are debt BDCs that hold 90% or more of their assets in debt investments. Realistically, most people buy BDCs for dividend yield, and debt investments are a better fit for generating routine income to afford large dividend payouts.

Based on past performance alone, Main Street Capital (MAIN 0.18%) is one of the best equity BDCs in the business today, and TPG Specialty Lending (TSLX 0.57%) is one of the best-performing debt BDCs. Both BDCs earn high valuations relative to their peers on virtually every metric.

Whether one type is better than another can be debated. For every Main Street Capital, there is an American Capital, an equity BDC that nearly went under during the financial crisis. And for every TPG Specialty Lending, there is a Fifth Street Senior Floating Rate, which has suffered from poor underwriting results despite a focus on optically less risky loans.

Some other factors worth exploring:

- Concentration: How much of the BDC's portfolio is tied up in its five or 10 largest investments?

- Industry focus: Some BDCs specialize in healthcare, and some invest only in venture-capital (tech) companies. Which industries make up the largest part of a BDC's portfolio, and how does that affect its riskiness? Concentration in oil and gas and in retail has not exactly been a good thing for BDCs in recent years, for example.

- Company size: Does the BDC invest in larger companies with professional management and sophisticated finance departments, or small mom-and-pop shops with weaker financial controls and reporting?

The BDC's operating structure

BDCs employ one of two basic operational structures. The vast majority of BDCs are externally managed, which means their investment portfolios are managed by an external company that makes investment decisions for the BDC and collects a fee for its services. A minority of BDCs are internally managed, and thus employees whom the BDC pays directly make the investment decisions.

- Ares Capital is an example of an externally managed BDC. It's managed by an affiliate of Ares Management, which collects a fee equal to 1.5% of its assets each year, plus an incentive fee equal to 20% of its pre-incentive fee returns in excess of 7% each year.

- Main Street Capital is an example of an internally managed BDC. Its employees collect a cash salary directly from the BDC, plus stock-based compensation. The payroll expenses are taken directly off the income statement.

There are advantages and disadvantages with either model, and we could spend all day debating which is better for investors. Ultimately, though, the best operational structure is one that fairly distributes a company's earnings power between insiders and outside shareholders.

The internally managed structure has been a boon for Main Street Capital, which is a particularly lean operator, but American Capital Ltd. used it to pay outsize salary and stock-option compensation. Likewise, the externally managed structure has been used for the benefit of shareholders at Golub Capital BDC (GBDC 0.55%), which has a fair fee arrangement that rewards good returns and punishes bad ones, and abused by Fifth Street Senior Floating Rate, which unnecessarily issued stock at dilutive prices to juice fees paid to its management company.

Some other factors worth exploring:

- BDC boards: Are the members of the board of directors truly independent from management? Do they have a significant stake in the BDC relative to their compensation as directors? Will they act in shareholders' best interests?

- Who owns the BDC: Individual investors typically, but not exclusively, hold shares of BDCs. However, individual investors aren't the best at keeping managers in check. BDC managers aren't afraid of angering retirees, but they typically won't step too far out of bounds if they know shareholders are watching more carefully. Significant institutional ownership can be a valuable protection for the individual investor.

How to value BDCs

BDCs are largely valued based on three metrics: dividend yield, net asset value (book value), and net investment income (shortened to NII).

- Dividend yields: These are calculated by dividing the stock's dividends on an annual basis by the share price. (A BDC that pays $1 in annual dividends and trades for $10 per share has a dividend yield of 10%.) Some investors like to use a BDC's dividend yield as a comparative data point. If a "safer" BDC yields 8%, a "riskier" BDC might need to offer an 11% yield before it becomes attractive to investors. Dividend yields can also be compared to other speculative credit investments, such as junk bonds. If a junk-bond ETF offers a 5% yield, a BDC that yields just 6% may be unattractive, given that the trade-off is more risk for a mere 1-percentage-point increase in yield. (BDCs' additional risk comes from their use of leverage to amplify returns, something a bond ETF or fund doesn't ordinarily use.)

- Net asset value (NAV): This is the textbook name for "book value" in the BDC industry. Many investors use NAV as a guide for a BDC's fundamental value. If a BDC trades for $9 per share and has a NAV of $10 per share, it trades at a price-to-NAV ratio of 0.9. It bears noting, however, that the BDC's board of directors determines the NAV, and thus it can be subject to some gamesmanship. It's not uncommon for BDCs to trade at a discount to book value because of expectations of future credit losses, high management fees, or a perception that managers don't have shareholders' best interests at heart. Simply put, when a BDC trades for less than NAV, the market is effectively saying that it doesn't value a dollar of equity the BDC manages as truly being worth $1.

- NII yield: BDC investors tend to use NII, the industry's widely used earnings metric, as a proxy for a BDC's earnings power. NII is how much a BDC earned in any period before capital gains and losses. Thus, NII yields and the price-to-NII ratio are used just as earnings multiples are used in other industries. Those who are familiar with bank reporting can look at NII as being roughly equivalent to a bank's pre-tax, pre-provision profit. Since over the long haul BDCs have historically generated losses in excess of gains, NII is really a "best case" measure of earnings.

Which valuation metric is best? Well, all of them have a place.

Dividend yields may not be very sophisticated -- if we could pick good stocks just by observing their yields, we'd all be rich -- but they work as a convenient rough metric for comparing one BDC to another.

NAV multiples have a lot of value as a sanity check. If we think of NAV as being the best-case valuation for a BDC's portfolio, paying a large premium on top probably isn't a good bet in the long run. Since many BDCs will issue stock when their shares trade at a premium, large premiums to NAV are unlikely to persist for long periods of time. If you were a BDC manager who earned a 2% annual management fee on assets, how long could you resist the temptation to sell $100 million of stock, borrow another $75 million, and earn $3.5 million of incremental management fees each year? For most, the answer is "not very long."

Conversely, some view NAVs as virtually meaningless, and in some cases, that may very well be the case. A BDC that reports a NAV of $10 per share and trades for just $3 per share should simply close up shop, sell off its portfolio, and send checks to shareholders for $10. But BDCs rarely liquidate or sell out to one another, and when they do, it's often at a price less than NAV. For that reason, valuing a BDC based on its theoretical liquidation value (its NAV) doesn't always make sense.

I think NII yields are one of the best all-around figures for valuing and comparing BDCs in most circumstances. NII yields are a little more nuanced than dividend yields, and they value BDCs based on their earnings power, which is a derivative of their NAV. The average tends to hover around 8% to 10%, with riskier BDCs trading for higher NII yields and safer BDCs trading lower.

Getting started with BDCs

This is a very simple primer on how to think about BDCs as an investment for your portfolio, but it hits on many of the key concepts that are important for spotting the differences in BDCs' investment portfolios, their operating structures, and the implied expectations embedded in a BDC's stock price.

Though BDCs are a tough nut to crack, the good news is that if you can understand one BDC, you can probably understand them all. At the most basic level, what they do, and how they report their results, doesn't differ all that much from one BDC to another.

Most of the biggest and best-established credit managers now manage a public or private BDC in one form or another. Earlier this year, Carlyle joined the list of well-known managers with publicly traded BDCs when it took TCG BDC public in an IPO. In the fourth quarter, KKR's Corporate Capital Trust is expected to join the public markets when it goes from a private to a publicly traded BDC.

BDCs are likely to dominate the list of Wall Street's highest-yielding stocks for a long time to come. Yield investors should get acquainted with them, as they will always be near the top of the list for stocks with the highest dividend yields.