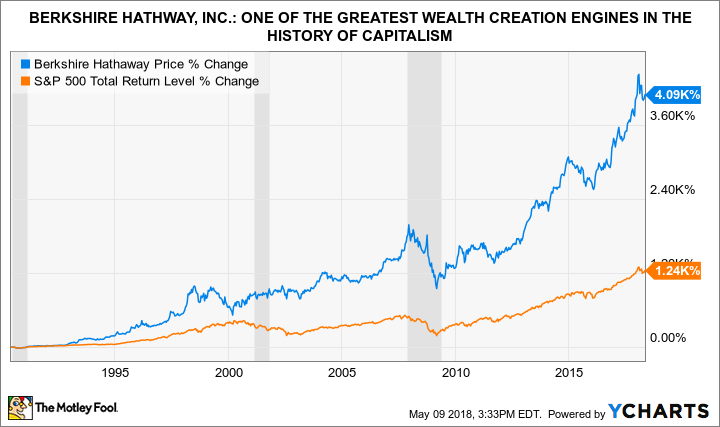

With Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. (NYSE: BRK-A) (NYSE: BRK-B) having just held its annual shareholder meeting last weekend (here are 5 key takeaways) and releasing its latest quarterly report, one question is topical: Is Berkshire Hathaway -- one of the greatest wealth creation vehicles in the history of capitalism (see graph below) -- a buy at current prices?

(Let me be clear about the scope of this article. I won't attempt to convince you that Berkshire Hathaway is a great business. My focus is the valuation of Berkshire Hathaway's common shares.)

Briefly, Berkshire Hathaway is a great business, or rather, it's a collection of (mostly) wonderful businesses that generate enormous cashflows -- roughly $400 million every week -- which can be deployed into new acquisitions (or public market investments) by a master capital allocator. If you want to understand what makes Berkshire so special, one of the best resources is Berkshire Hathaway's 50th Anniversary shareholder letter. I can't recommend highly enough three sections: 'Berkshire Today', 'The Next 50 years at Berkshire' and 'Vice Chairman's Thoughts-Past and Future' -- those fifteen pages are an invaluable foundation for potential Berkshire investors.

Source: Getty Images.

In trying to pin down whether or not Berkshire Hathaway's shares offer value, it's worth leaning on the clues provided by a super-investor who understands the company better than anyone alive -- Warren Buffett, himself, naturally! In the 2012 shareholder letter, Mr. Buffett wrote [the emphasis is mine]:

The third use of funds-repurchases-is sensible for a company when its shares sell at a meaningful discount to conservatively calculated intrinsic value...

We originally said we would not pay more than 110% of book value, but that proved unrealistic. Therefore, we increased the limit to 120% in December when a large block became available at about 116% of book value.

But never forget: In repurchase decisions, price is all-important. Value is destroyed when purchases are made above intrinsic value. The directors and I believe that continuing shareholders are benefited in a meaningful way by purchases up to our 120% limit.

At the end of February, speaking on CNBC, Buffett went further still:

We know that we're doing the continuing shareholders a favor if we buy it at that price [120% of book value]. And then that gets increasingly more questionable as you move along from there. Obviously I leave some margin of safety when I do the 120%, and if we were going to spend a lotta money to buy in stock at some time in the future, and it was 125% or 127% or something like that, we'd probably go that direction.

To recap: At 120% of book value, Berkshire Hathaway's stock price has a margin of safety -- it reflects "a meaningful discount to conservatively calculated intrinsic value" and Buffett would be willing to pay up to 127% of book value for a significant slug of shares.

The latest financials, published on Saturday morning, show a book value at the end of the first quarter of $211,184 per class A share, or $140.79 per B share; Wednesday's B share closing price of $199.64 thus equates to a price-to-book value multiple of 1.42 -- a 18% premium to Buffett's "formal ceiling" multiple of 1.20 and a 12% premium to his "informal ceiling" multiple of 1.27. At that price, do the shares still offer good value?

The answer is 'yes'. A 12% or even a 18% premium isn't enough to close the "meaningful discount to conservatively calculated intrinsic value". How can I be so certain of this? Answer: Buffett's business conservatism and his unwavering commitment to requiring a true "margin of safety" when he invests (whether it be in Berkshire's own shares or any others!). As he explained in The SuperInvestors of Graham and Doddsville in 1984 [my emphasis]:

You also have to have the knowledge to enable you to make a very general estimate about the value of the underlying businesses. But you do not cut it close. That is what Ben Graham meant by having a margin of safety. You don't try and buy businesses worth $83 million for $80 million. You leave yourself an enormous margin. When you build a bridge, you insist it can carry 30,000 pounds, but you only drive 10,000 pound trucks across it. And that same principle works in investing.

In sum, you can, right at this moment, buy shares of Berkshire Hathaway at a price that is somewhat below their intrinsic value. And while the current degree of undervaluation, which may be small, isn't sufficient to induce Buffett himself to repurchase the shares, it's enough to produce satisfactory returns for investors who are willing to hold the shares for an equity-appropriate timeframe (3-5 years, at a minimum). Furthermore, in a market that looks pretty expensive, the shares are highly likely to outperform -- at low risk -- the S&P 500 by several percentage points, on an annualized basis. What more can an investor ask for?