Vale (VALE -2.51%), based out of Brazil, is one of the biggest names in iron ore, competing with giants like Rio Tinto and BHP (BHP -2.31%). If you are interested in the space, Vale is easily one of the most important names to consider. And right now, the stock looks like a bargain. But there's so much more to understand before you jump on this relatively cheap iron ore giant. Here's a quick primer on what you need to know.

It is cheap

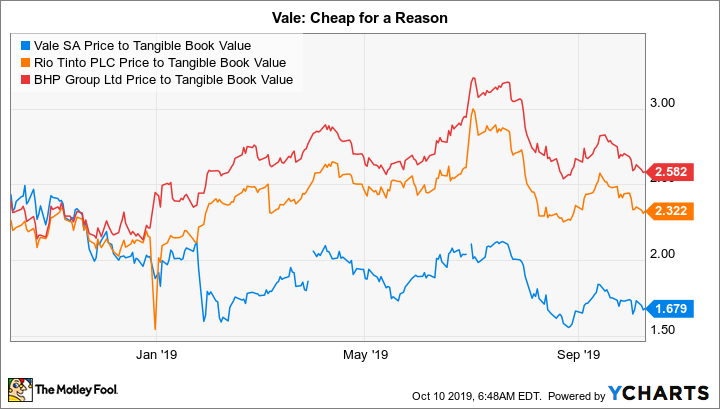

Before looking at why, let's agree that Vale's stock is on the sale rack. Shares have fallen roughly 28% over the past year, while Rio Tinto and BHP are off 1% and 3%, respectively. Clearly, investors are much less negative about Rio and BHP today.

Image source: Getty Images.

That disparate performance, meanwhile, has pushed Vale's price-to-tangible-book-value ratio down to around 1.7 times. A year ago it was roughly in line with its two most prominent peers. Rio's ratio is at around 2.3 times, with BHP's coming in at nearly 2.6 times. It is impossible to deny that Vale is cheaper than its closest rivals. Only there's a very big "but" coming.

One area where Vale falls well short, however, is dividend yield. Peers Rio and BHP offer yields of 6.1% and 5.6%, respectively. Vale's yield is zero since it eliminated its dividend in early 2019. Which leads us into the big question: Why is Vale so cheap?

It just keeps getting worse

In late 2015 a mine owned 50/50 by Vale and BHP had a waste dam collapse in Brazil. It was headline news, since the disaster at the Samarco mine destroyed nearby towns and nearly 20 people died. It was a terrible event that probably shouldn't have happened. The costs to clean up and make reparations was expected to be large, but manageable for the two owners.

Then, in early 2019, there was another waste containment dam break, this time at Vale's 100% owned Brumadinho mine (again in the miner's home country of Brazil). Nearby towns were destroyed, and this time nearly 250 people died. It was a far more deadly event and has set off a legal and regulatory chain reaction that hasn't been completed yet. The Brazilian government and people appeared willing to accept the first event as an unfortunate mistake, but a second in such a short time has, justifiably, set off alarm bells.

To its credit, Vale acted quickly. It shut down production at key assets and undertook a review of its mining portfolio to ensure all its facilities were safe. The outcome was that there were some more high-risk containment dams that needed to be dealt with. The company also chose to part ways with key leadership and, as noted above, eliminated the dividend. These were all good moves that showed the miner was serious about mending its ways.

VALE Price to Tangible Book Value data by YCharts

But trust has been lost. On Wall Street that's meant a falling stock price. The problem is that the story is far from over and Vale appears to have lost the trust of Brazilian citizens, regulators, and authorities. In fact, the second disaster has even led to more questions about final settlements for the first disaster (the cost of which could be over $40 billion, split between Vale and BHP).

Vale has been accused of knowing there were problems and choosing to do nothing about them. Most recently, Brazilian police have recommended that criminal charges be brought against the company and key employees. With courts already involved, freezing the company's assets and ordering operational shutdowns, this new legal development takes events to a new level of bad. Risk is high here and so is uncertainty. That's a very worrisome combination, since it means that just about anything could happen. And in Vale's case "anything" is likely to be bad.

The company's second-quarter earnings were likely just a preview of what the future could hold. Vale's EBITDA fell nearly $850 million because of the work stoppage prompted by the Brumadinho mine disaster. That's not great, but impacts like this are probably going to be temporary. However, it also took a $1.5 billion provision for reparations and other costs associated with the event. But if you look at the smaller Samarco disaster as a guide, Vale and BHP settled with the government for roughly $7 billion. And the pair still has to deal with a civil lawsuit of over $40 billion (which has been stalled by the events at Brumadinho). It's highly unlikely that the roughly $2.4 billion hit in the second quarter is the end of this story.

That said, every quarter won't contain numbers like this because courts don't work on a quarterly schedule. Vale, meanwhile, is likely to report "adjusted" EBITDA in the future, which will likely pull out very real costs like these. But it is hard to believe that there won't be more and larger costs associated with this disaster, some of which are likely to be paid over time because they are so large. And that means the impact of Vale's mining disasters will probably linger for years.

Avoid this miner

An old maxim for value investors is that you should buy when everyone else is fearful. That's true sometimes, but not all the time. You have to look at why investors are fearful and assess if that fear is justified or not. In Vale's case, the fear is spot on.

The best outcome from this pair of disasters would be that Vale has to absorb the (likely huge) cost of improving its facilities and reparations (the final figure isn't close to being determined yet). And that will happen only after years of legal costs and bad press. The worst case is that the miner goes out of business. While that worst case isn't likely, the news flow suggests that the situation is getting worse and not better for Vale. Until there's much greater clarity, most investors should avoid this name, no matter how cheap it gets compared to its peers.