The past year has been an especially bizarre one for investors. The COVID-19 pandemic drove the economy into a deep recession this spring. At first, the stock market reacted as one might expect: by late March, the S&P 500 had fallen 30% in 2020.

Since then, low interest rates, a flood of liquidity, and growing excitement about the transformative potential of many technology companies have powered a remarkable rally. By the end of the day on Wednesday, the S&P 500 was up 14% for the year. The tech-heavy Nasdaq-100 has fared even better and is up 45% year to date. Even that pales in comparison to the performances of some companies that have prospered in 2020. Zoom Video Communications (ZM -0.55%) stock has surged 466% this year, while Tesla (TSLA -0.05%) stock has rallied 669%.

Tesla, Zoom Video Communications, and index year-to-date performance, data by YCharts.

Investors shouldn't get carried away celebrating these gains, though. Unless you have high risk tolerance and an extremely long investment horizon, the end of 2020 might mark an opportune time to lock in some gains in the biggest stock market winners of 2020, rather than getting greedy for even more upside.

Rallies can fall apart rapidly

Cisco Systems (CSCO -0.78%) is a great example of an excellent business that became a terrible stock after rallying too far.

Cisco was a market darling in the late 1990s due to its dominance in networking. As investors came to recognize the massive potential of the internet and the networking giant's central position in that ecosystem, Cisco stock rallied more than 2,600% between the beginning of 1995 and the end of 1999. The stock then rallied another 50% in the first three months of 2000. Cisco even briefly held the title of most valuable company in the world.

Cisco stock performance, data by YCharts.

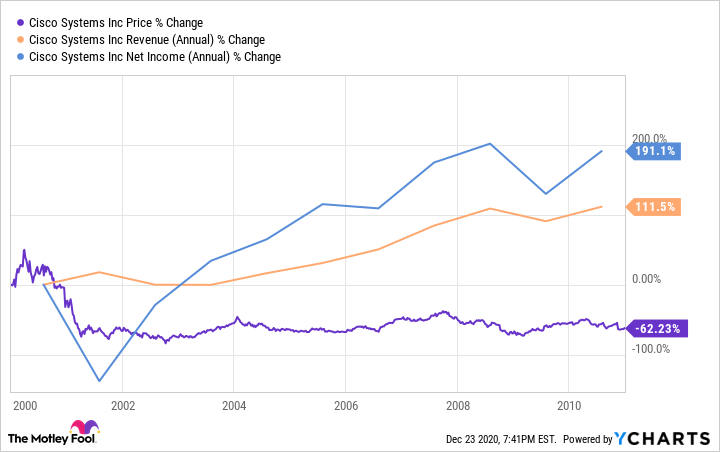

It was all downhill from there. By the end of 2000, Cisco stock had surrendered all of its gains from early in the year. The sell-off deepened in 2001. Ultimately, the stock ended 2010 62% below where it stood 11 years earlier. (Investors who bought at the peak in March 2000 and never sold are still waiting to reach breakeven).

Importantly, this huge stock market wipeout didn't stem from the business falling apart. From 2000 to 2010, Cisco's revenue more than doubled and net income nearly tripled, despite two recessions (including the bursting of the dot-com bubble and the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression).

Cisco revenue, earnings, and stock performance, data by YCharts.

What it means for investors

As a general rule, investing in great companies (rather than the cheapest stocks) and exercising patience are two key factors for achieving excellent long-term returns. However, the example of Cisco highlights how you can invest in a great company very patiently and still wind up with awful returns if the starting valuation is way too high.

Diversification can help -- a bit. But many late-1990s market darlings that appeared to be great businesses at the time posted similarly bad results. Even if you had a few winners, it would have been very easy to own a portfolio that posted negative returns for the decade from 2000 to 2009. (Amazon.com stock, for example, rose just 77% over that period.)

Thus, it's important to think carefully about your personal risk tolerance and investing time horizon. It's easy to get sucked into recency bias by giving undue weight to recent events relative to events further in the past. For nearly a dozen years, every big stock market drop has been a buying opportunity, with stocks fully recovering their losses in months (or even weeks). Yet that doesn't always happen. It's also possible to own shares of great companies and suffer losses that can take decades to claw back.

If you have a very high risk tolerance and you can afford to hold stocks for decades, perhaps you can reasonably overlook the risk of an extended slump for growth stocks. If not, you may want to take a look at your holdings and lock in some gains on your 2020 highfliers.

Two examples

Zoom is one company at risk of being the next Cisco for investors. Revenue has more than quadrupled year over year in each of the last two quarters, leading to bumper profits. However, Zoom was uniquely well positioned to benefit from the pandemic. Some customers will undoubtedly find more uses for Zoom over time and will continue to increase their spending with the company. Others, though, may find that they don't use Zoom as much after the pandemic and spend the same or less in the future.

Image source: Getty Images.

It's certainly possible that Zoom will find new avenues for growth and increase its earnings tenfold over the next decade. But it's also quite plausible that it will "only" triple its earnings (as Cisco did between 2000 and 2010). That scenario would likely result in negative returns between now and 2030.

As for Tesla, it delivered nearly 140,000 vehicles in Q3, giving it an annual run rate about 50% higher than its 2019 delivery total. Its operating margin approached double-digit territory, despite a big jump in stock-based compensation expense. While regulatory credits accounted for nearly half of its operating profit, the company is solidly profitable and cash-positive without them. Tesla is on track to grow rapidly for years.

But Tesla stock trades for about 282 times its projected 2020 earnings, while most legacy automakers trade for less than 10 times earnings, due to the sector's cyclicality and brutal competition. If that valuation multiple contracts toward the industry average as Tesla matures, the stock could wind up lower than it is today even if revenue surges tenfold over the next decade and the company's operating margin expands to 13%-15%.

None of this is to say that Zoom or Tesla are necessarily bad investments. The point is that for these companies and many others like them, it would not be surprising for the stocks to post negative returns for a decade or more, even if the businesses perform well by ordinary standards. Be realistic about whether you can assume that risk. If not, it might be time to take some money off the table.