Boeing (BA 0.14%) and General Electric (GE -0.69%) are major suppliers of aerospace equipment, and their ultimate end demand comes from airlines that purchase planes. It's a great industry to invest in, but there is one logical problem with it: Historically, airlines don't actually cover their cost of capital.

This would seem to make stocks of aerospace suppliers ones to avoid, but the truth is very different. Here's the lowdown on a fascinating industry.

Airlines aren't productive (at least for shareholders)

The ultimate test of whether a company is allocating capital productively for shareholders is the comparison between its return on invested capital (ROIC) and its weighted average cost of capital (WACC). The former is simply the profits generated from the capital invested in the business, while the latter is the weighted cost of its equity and debt.

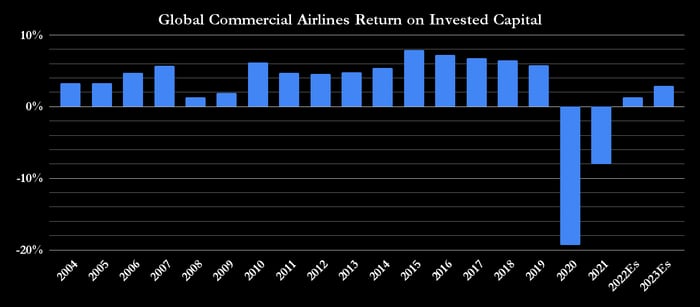

The problem in the global airline industry is that it has historically not been good at generating ROIC. The chart below shows global airlines' ROIC since 2014 and includes the disastrous recent period when pandemic-related lockdowns were in force.

It also shows the golden period between 2015 and 2019, when relatively high ROIC and relatively low interest rates gave hope that the industry could generate value for shareholders.

Here's how the International Air Transport Association (IATA) argues that historically, ROIC hasn't exceeded WACC, and "the air transport industry has struggled to deliver the returns which equity investors expect for risking their capital."

The IATA also notes, "At the regional level, however, equity investors in Europe and North America did receive returns in excess of the cost of capital over the 2016-2019 period."

Data source: International Air Transport Association.

That said, not all airlines are made equal, and neither are all regions. According to IATA estimates, the North American region -- and to a lesser extent, Europe -- is making a stronger return to profitability.

|

Net Profit |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 (Est.) |

2023 (Est.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Global |

$26.4 billion |

($137.7 billion) |

($41.9 billion) |

($3.6 billion) |

$9.8 billion |

|

North America |

$17.4 billion |

($35.1 billion) |

($2.3 billion) |

$9.1 billion |

$11.5 billion |

|

Europe |

$6.5 billion |

($34.5 billion) |

($12.1 billion) |

$4.1 billion |

$5.1 billion |

|

Asia-Pacific |

$4.9 billion |

($44.8 billion) |

($14.6 billion) |

($13.5 billion) |

($6.9 billion) |

Data source: International Air Transport Association.

Why invest in the aerospace sector?

A quick look at the chart above shows that the IATA estimates global airline ROIC will only be 2.9% in 2023, which will not cover WACC, and certainly not in the current rate environment.

All of which leads to the question directly above. Some of the answers, at least from an equity holder's perspective, are as follows:

- Equity investors are intrigued by a glamorous and essential industry and enjoy picking winners from it.

- As noted above, just as there are regional winners and losers, there are also good and bad airlines.

- The 2015-2019 period heralded a new era of airline profitability, and the prospect of long-term growth in Asia held out the hope of all regions contributing to global airline profit growth.

These arguments describe the equity investor's perspective, but it's arguably more important to look at the perspective of capital providers. Lending to airlines is attractive because the loans can be securitized by the airplanes themselves -- assets that tend to have a long life. And airplanes can be leased to airlines through special purpose vehicles (SPVs), meaning that if the airline defaults, the lenders can simply repossess the airplane without the messy business of making claims on the airline.

Image source: Getty Images.

What about the aerospace suppliers?

As such, the industry can, cynically, be seen as profitable for bondholders but not so much for equity holders. It's also a great industry for aerospace suppliers, and you only have to look at Boeing's multiyear backlog to see the level of demand out there.

For example, it has 4,215 unfilled orders for its 737 but only plans to deliver 400 to 450 this year. That's almost a decade of backlog at the current production rate.

It's a similar story for General Electric. The company and its joint ventures provide the engines used on three out of four flights. As of the end of March, GE Aerospace had a $350 billion backlog, and more importantly remaining performance obligations (or unfilled customer orders) of $137.4 billion, compared to revenue of $26 billion in 2022.

There's little doubt that end-market demand for airplanes remains strong and is recovering well from the lockdowns. It's a testimony to the attractiveness of the industry, even if the airlines themselves aren't that good, on a global basis, at generating value for shareholders.