This article is the first in a series. The second article focuses on CLIP's materials capabilities and more.

I was fortunate to conduct a phone interview last week with a prolific inventor and serial entrepreneur, Carbon3D CEO Joseph DiSimone. Carbon3D made a splash in the tech world in mid-March, when DiSimone unveiled and demonstrated the company's seemingly game-changing 3D printing technology, Continuous Liquid Interface Production, or CLIP, at the TED 2015 conference, while simultaneously CLIP appeared as the cover story in Science magazine.

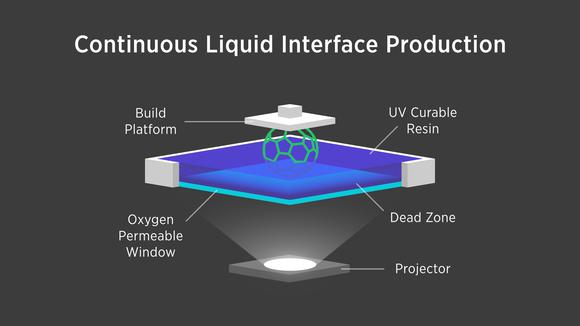

CLIP harnesses UV light and oxygen to "grow" polymer parts continuously at speeds 25 to 100 times faster than the leading 3D printing technologies. Additionally, CLIP can produce objects that have a smoother surface finish than conventionally 3D-printed parts and a structural consistency on par with injection-molded ones, according to Carbon3D.

CLIP is generating a lot of buzz because it has the potential to disrupt the global manufacturing sector. That's because speed, surface quality, structural integrity, and materials capabilities (the focus of the second article in this series) are key hurdles that have been holding 3D printing back from moving beyond prototyping and select, short-run production applications into a greater array of manufacturing applications.

T-1000 from Terminator 2. Source: Wikipedia.

Investing is largely about betting on the jockey

If you've read about CLIP, you know that its three inventors were inspired by T-1000 from the movie Terminator 2, which rises from a pool of liquid metal to assume the form of any person or object. That's a made-for-headlines snippet, but I wanted to know more about the inspiration and invention process.

Besides being curious, there was a practical reason: I thought hearing DiSimone expound on this topic could give us a better glimpse into the thought processes of those running Carbon3D -- he and CTO Dr. Alex Ermoshkin, a physicist and co-inventor of CLIP (the third inventor being DiSimone's fellow chemistry professor at UNC-Chapel Hill, Edward Samulski). After all, when it comes to investing, we're largely betting on the jockey(s).

Granted, Carbon3D is privately held, but if the commercialized technology functions nearly as well as the company purports and the cost of a machine -- the initial one is due out within one year -- isn't stratospheric, there should be public company investing ramifications. These could range from Carbon3D's going public itself or partnering with a public company to the potential effects on 3D printing companies Stratasys (NASDAQ: SSYS), 3D Systems (NYSE: DDD), and voxeljet (NYSE: VJET), all of which are involved in the enterprise-focused plastics space. There could also be potential ramifications for those involved in plastic injection molding, such as quick-turn, on-demand manufacturer Proto Labs (NYSE: PRLB).

Carbon3D is racking up some big funding, which increases its potential as a competitive threat. In addition to the $41 million it's received from venture capital firms, leading design software maker Autodesk (NASDAQ: ADSK) recently backed Carbon3D with a $10 million investment from its Spark Investment Fund.

DiSimone: "Patents drive innovation"

DiSimone told me that he was introduced to 3D printing in the early 2000s through the corrective orthodontics field. Then in 2012, as a chemistry and chemical engineering professor, he was approached by his former post-doc student Ermoshkin about starting a 3D printing company. DiSimone told Ermoshkin to come back to him after he had searched the patent literature using five or six specific keywords. Ermoshkin performed the search and reportedly returned to DiSimone dejected, as the number of patents he found approached 1,000.

After reading through all the patents, however, it became increasingly clear to the inventors that "nobody was doing anything continuous" -- and so they started to think about how they might do that.

Source: Carbon3D.

DiSimone said they knew they wanted to have the 3D-printed part rise out of a puddle of resin, just like T-1000 rises out of a puddle of liquid metal. From there, the brainstorming led to how CLIP accomplishes its Terminator-like feat: Through the use of a transparent, oxygen-permeable window that's something like a contact lens, CLIP technology controls the exposure of UV light and oxygen to the UV-light-curable resin. The UV light solidifies some parts of the resin while the oxygen prevents the layer bordering the window -- the "dead zone" -- from solidifying. This process allows for the object to "grow" from the bottom up in a continuous process.

After the basic idea came to them, Ermoshkin built a prototype -- "something he's really good at," commented DiSimone, who then added that the inventors knew they were on to something during the initial trial run.

During his mention of the patent search, DiSimone -- who has 150 issued patents -- stated that "patents drive innovation." Indeed, without patents, there would be much less incentive for individuals and entities to innovate, as it would be foolish to spend resources if others were allowed to profit from the get-go.

Building upon past innovations

CLIP technology is similar to stereolithography, or SLA, which was invented in the mid-1980s by Chuck Hull, who then went on to found 3D Systems. The key difference is that SLA pauses between producing each layer, whereas CLIP operates continuously, thanks to the oxygen-enriched "dead zone."

What might seem like a small tweak to an existing technology results in changing 3D printing from a mechanical process into a tunable photochemical one. This results in a greatly revved-up process -- as DiSimone demonstrated at TED -- and, according to Carbon3D, greater structural consistency of the printed object, and the opening up of a wider range of materials possibilities.

The signs of a successful CEO?

DiSimone has straddled the academic and private sectors for almost his entire career. He's clearly driven to apply what he learns in his DiSimone Research Group to solve real-world issues. He's already successfully done so multiple times, having leveraged his polymer chemistry expertise to create such diverse products as an environmentally friendly dry-cleaning solvent and nanocarriers for vaccines. These inventions led to spin-off companies Micell Technologies and Liquidia Technologies, respectively.

It struck me that DiSimone's telling one of his co-inventors to run a patent search for specific keywords before even discussing starting a 3D printing company seemed a shrewd, practical approach to maximize potential returns while limiting wasting resources. This trait should serve him well in his CEO role.

While DiSimone and Samulski are chemists, physicist Ermoshkin rounds out the founding trio. DiSimone's a big believer that there can be wonderful synergy among people with different strengths and backgrounds. This belief put into practice at Carbon3D should help the company as it scales up to compete in an increasingly competitive space.

My thanks to Joe DiSimone, as well as Kristine Relja and Jennifer Gentrup, who coordinated this interview.