Before many major federal projects can be started in the U.S., whether new commercial construction or modification of an existing building to meet wholly different needs, an environmental impact assessment (EIA) often must be completed. Although less complicated than an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS, a more detailed and expensive regulatory sibling), the EIA requires examining the potential impacts of a project on the natural environment, as well as to the people who may live near it.

Some people might consider the EIA as just another bureaucratic waste of time, but spending the energy to perform one can actually save a lot of effort on the back end of a federal project. Instead of dealing with potential slowdowns or work stoppages when environmental, cultural, or social impacts are uncovered in the middle of a project, an EIA can help better inform the real estate project’s trajectory and can be used to avoid a lot of problems.

Understanding an Environmental Impact Assessment

EIAs are regularly used in place of the more complicated (and costly) EIS. Both are commonly utilized to better inform interested parties about the effects of a federal project, but the EIA can be considered a standalone item if the project doesn’t pose serious environmental impacts, and it reduces the time and money involved in such an endeavor.

Agencies can’t simply skip an EIA because they don’t think it’s necessary -- the EIA is there to determine what might have a significant impact on the area around the project site. This might include any kind of impact, from upsetting wildlife breeding grounds to disrupting human remains, changing how water moves, or destroying the flow of established neighborhoods.

EIAs have been used in the U.S. since the 1960s, but they received formal recognition with enactment of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1969. The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) now oversees most of the day-to-day work related to NEPA. The CEQ doesn’t have enforcement authority, but it can refer violators to the judicial system.

Since its adoption in the U.S., more than 100 nations have set similar standards based on NEPA. Even the United Nations has a guide for best practices in EIAs that attempts to unify the body of worldwide legislation on EIAs into a gold standard.

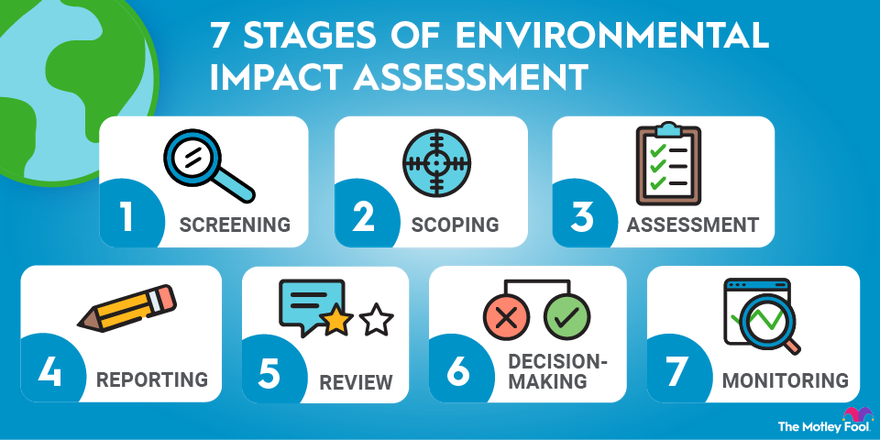

Stages of an Environmental Impact Assessment

There are generally seven stages of an EIA. These steps can vary slightly, or sometimes take place simultaneously, depending on the specific circumstances involved. But in general, you can expect that each of these stages will be involved in some way in an EIA:

- Screening: Not every project will need an EIA, so screening is done prior to investing the labor and time in the assessment. The projects requiring an EIA will vary depending on the country and how much is already known about potential impacts.

- Scoping: Generally, an EIA will cover a limited number of key issues, developed with the input from the public, as well as with non-governmental organizations. Scoping will also look at similar activities nearby and their impacts and identify problems that need to be addressed before they become roadblocks to success.

- Assessment/evaluation: During the evaluation and assessment phase, the goal is to take the scope previously identified and determine the likely magnitude of the impact from each item on the list. If the change to the environment is determined to be unacceptably high, alternative solutions are explored, including (but not limited to) canceling the project. Mitigation is the primary goal, but if the changes can’t be blunted to make the project less impactful to the community or environment, determining that the project isn’t feasible early on is better than waiting until significant resources have been dedicated.

- Reporting: If the project makes it to the reporting phase without too many serious bumps, the main report is put together. An environmental management plan (EMP) and a non-technical summary designed for the public are prepared. It’s really important this step be done well since it sets up the rest of the process.

- Review: At the review stage, everyone gets a say about what’s been prepared so far. Anyone who may be affected within the scope of the reporting, including the public or local or national authorities, will be asked for participation in reviewing the quality of the report.

- Decision-making: Once the report has been compiled and scrutinized, it’s time for decisions to be made about how the project should proceed. Relevant authorities will decide if the project can be accepted as is, if changes should be made, or if it should be deferred or rejected entirely. Approvals are often subject to conditions based on the EIA.

- Monitoring and compliance: The final stage of any EIA is monitoring and checking compliance with the conditions outlined in the final approval. When all things are as they should be, this step is useful in understanding how well projections about the project lined up to reality. Monitoring can also help get ahead of unpredictable changes or unanticipated impacts of the project so they can be addressed quickly.

Strategic Environmental Assessment

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is often performed before an EIA in some places, and it has much the same structure. The SEA is often incorporated into a final EIA. SEAs are meant to be more of a strategic overview for policy at both the local and national level.

If an EIA looks at a project and how its effects radiate outward into the environment and culture, an SEA looks at policies and planning and how those influence the whole area. An EIA might look at how a building near a breeding ground for seals will influence seal populations, but a SEA will look at how policies about building near the same breeding grounds could change outcomes.

Related investing topics

The bottom line

An environmental impact assessment can be a vital tool for a federal project, but it also requires significant time and effort to compile, as well as time to get community feedback. Projects that require EIAs may move very slowly, but the hard work is being done ahead of time to avoid potentially costly and disastrous delays later.